The Past, Present, and Future of Resident Evil: All Roads Lead to Raccoon City Part 1

Presenting the first piece of our ongoing retrospective on Capcom’s iconic survival horror franchise.

The last year has been an exciting one for Resident Evil fans. 2019 saw not only the release of the long-anticipated Resident Evil 2 remake, but also the announcement that Resident Evil 3 will be getting the same treatment (along with the Resistance multiplayer spin-off) right around the corner as well. As we approach the April reimagining of Jill Valentine’s last escape, we thought it would be fun to take a look back at the series’ roots, in particular the original trilogy set in and around the fictional town of Raccoon City, where it all began.

From a remake of a Famicom game, to a scrapped sequel rebuilt from the ground up, and then a third game which wasn’t even meant to be a part of the original trilogy–all of which have now been reenvisioned–here’s the story of how survival horror took the world by storm and gave birth to a paramount franchise.

Part 1: Enter the Survival Horror

The original Resident Evil began development all the way back in 1993 and was initially conceived as a remake of Capcom's Sweet Home, a 1989 horror-themed role-playing game for the Famicom based on a movie of the same name. It is often considered the first true survival horror game and is directly responsible for the creation of this beloved franchise.

Then junior game developer Shinji Mikami, who had up to that point only worked on Disney-licensed properties including Goof Troop and Aladdin for Super Nintendo and Who Framed Roger Rabbit for Game Boy, was chosen by Sweet Home’s original director Tokuro Fujiwara, to take charge of this project to be released on the brand-new Sony PlayStation. Mikami was initially against leading development since he wasn’t a fan of being scared, but Fujiwara insisted this was exactly the reason he was entrusting him with the project, since he innately knew what would scare gamers.

Mikami spent the first six months of production working on the game alone, writing a 40-page script and creating concept and character sketches. Resident Evil was initially conceived as a first-person horror shooter with a focus on psychological scares, inspired by the combat screen in Sweet Home. However, this idea was abandoned after Mikami played 1992’s Alone in the Dark, leading to the cinematic fixed camera angles in the third-person perspective along with the infamous tank controls.

Despite this change, many other gameplay elements from Sweet Home were adapted for the project, including the mansion setting, careful inventory management, puzzles, and even the door-opening animations which became a staple of early Resident Evil games. Over time, the project evolved so much that it ceased to be a straight remake of Sweet Home and was consequently turned into an entirely new property called Biohazard.

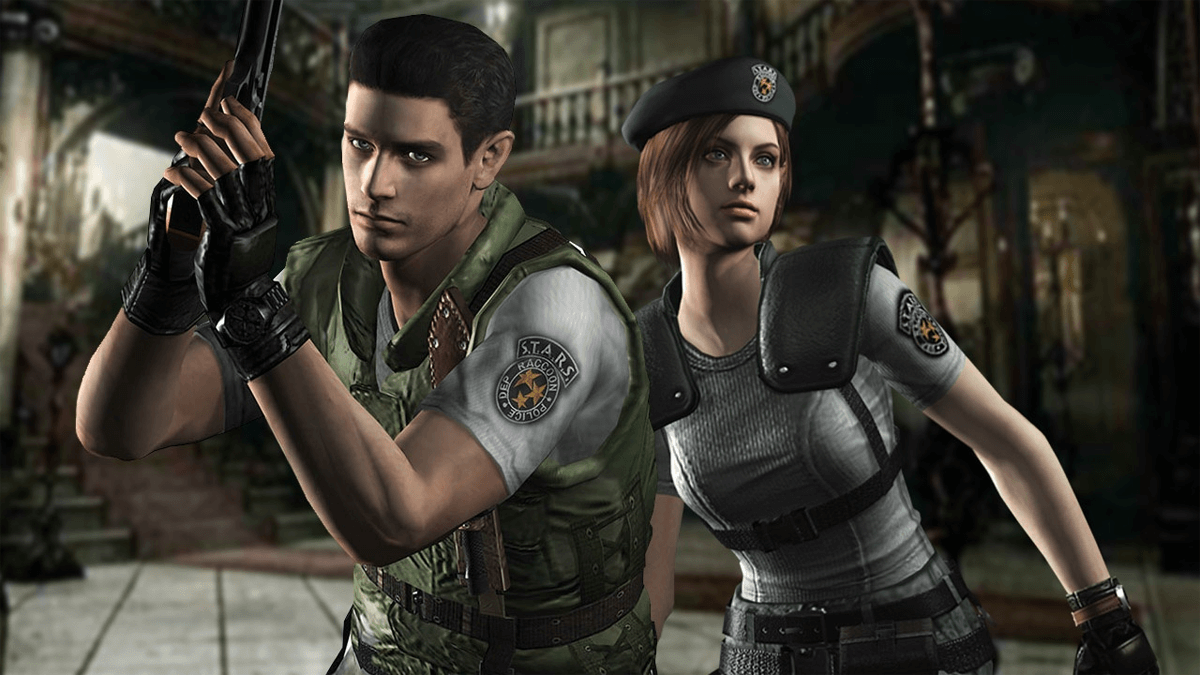

The story focuses on a group of special operations police officers called S.T.A.R.S. (Special Tactics and Rescue Squad), a branch of the local Raccoon City Police Department. The division’s Bravo Team had been sent into the nearby forests of the Arklay Mountains the previous night to investigate a string of grisly cannibalistic murders and disappearances, although their helicopter had suffered a malfunction and crashed. The Alpha Team is then sent out to find their now-missing compatriots.

After being abandoned by their helicopter pilot, Brad Vickers, team members Chris Redfield, Jill Valentine, Barry Burton, and Captain Albert Wesker are forced to flee into a nearby mansion with a group of zombified dogs in pursuit. Players take on the role of either Chris or Jill, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, as they become separated and begin to search the Spencer Mansion for a way out, fighting against zombies and other infected creatures while navigating the mansion’s many intricate traps and puzzles.

Throughout the course of the game it is revealed that the international pharmaceutical company, Umbrella Corporation, is using a lab hidden under the mansion to develop Bio-Organic Weapons through the use of the T-Virus. This virus is the cause of all the monsters encountered in the mansion, and infects, kills, and mutates any living creatures it comes across.

Some creatures, such as the Hunters, have even been created purposefully by researchers to explore the practical applications of the virus. Not even plants are immune to its effects, as Chris and Jill are forced to deal with the carnivorous Plant 42. Umbrella has even infected sharks to see what the T-Virus would do to the primordial killers, only for them to break free of their enclosure and wreak havoc in the mansion’s bunk house.

Captain Wesker is eventually revealed to be a former Umbrella researcher and an undercover agent planted to keep tabs on local law enforcement, mainly to prevent them from implicating those behind the research or interfering with company operations. Wesker is also personally responsible for luring the S.T.A.R.S. into their current predicament in order to collect combat data on how these highly-trained officers deal with the fruits of the T-Virus, even blackmailing Barry into assisting him by threatening his family.

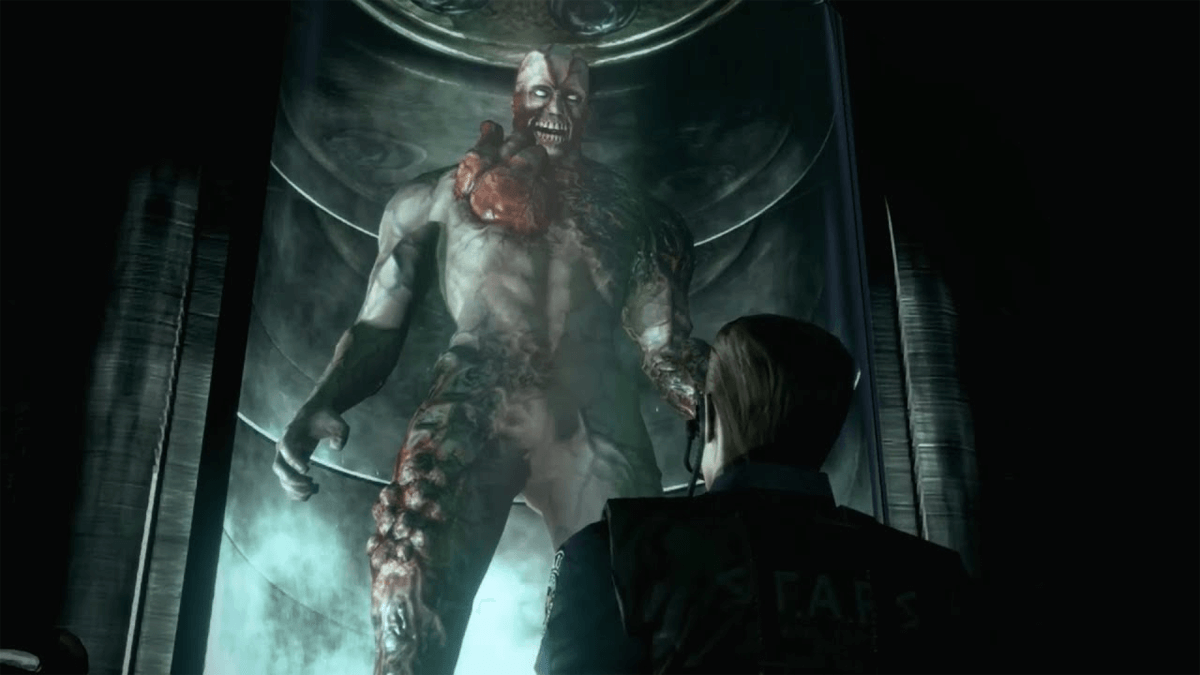

In the end, Wesker unveils Umbrella’s ultimate B.O.W., the massive clawed Tyrant, which is released and seemingly kills the treacherous captain. Alpha Team pilot Brad Vickers returns at the last moment, enabling the death of the Tyrant and the escape of Chris, Jill, Barry, and sole-surviving Bravo Team member Rebecca Chambers as the mansion self-destructs.

After three years in development, Biohazard was ready to be released to the world in 1996. In North America, the localization team changed the title to Resident Evil, possibly to avoid a legal dispute with a popular band of the same name. Capcom didn’t expect the game to be anything more than a modest success, hoping it would sell around 200,000 copies. Instead, the game went on to sell 2.75 million units and was a best-seller in both North America and Europe.

Resident Evil Director’s Cut was then released in 1997 featuring various updates, followed by a version that utilized the PlayStation’s new DualShock controller in 1998. These two versions combined sold another 2.33 million copies. It seemed no matter how many times Capcom released the game, it would continue to sell. Players had their first taste of this new “survival horror” genre, a term coined by the publisher itself, and they couldn’t wait to get their hands on more.

The original Resident Evil has had numerous ports and releases over the years on several different platforms, often changing or adding minor details. Besides the previously mentioned Director’s Cut and DualShock versions, the game was also ported to the Sega Saturn, adding a battle mode and some unique enemies. The PC version included two exclusive weapons and the ability to skip the door opening scenes.

Interestingly, a Game Boy Color version was in the works from developer HotGen for release around 2000, although it was later cancelled due to the hardware limitations of the handheld platform. In 2012, a ROM of the unfinished Game Boy Color prototype was leaked and features almost every detail from the original version. It’s definitely a curiosity worth checking out.

The game did eventually receive an enhanced portable version on the Nintendo DS in 2006 dubbed Deadly Silence, which added new features such as the Rebirth Mode and local multiplayer. It also took advantage of the system’s various unique peripherals, for example using the top screen for the map and allowing the touchscreen and stylus to be used for knife attacks.

Admittedly, while important in the history of video gaming, Resident Evil did not age as well as its sequels. From the cheesy live-action cutscenes filmed with whatever actors Capcom Japan could get their hands on, to the broken and nonsensical English voiceover performances, it became difficult to not make fun of the “Jill sandwich” or “master of unlocking” lines and had obviously dated visuals in a post-Resident Evil 2 world. Shinji Mikami felt the same way, so after Capcom struck an exclusive deal with Nintendo to bring Resident Evil over to the GameCube, he set out to direct a remake of his original creation.

Capcom had already ported Resident Evil 2, Resident Evil 3: Nemesis, and Resident Evil Code: Veronica X to the console, and development had also begun on a prequel, Resident Evil Zero, which had originally been planned as a Nintendo 64 exclusive but was eventually delayed and moved to the GameCube due to the performance limitations of the N64’s cartridge system. Mikami wanted to make a version of his classic game that would appeal to both new gamers and veteran fans alike.

Development on the Resident Evil remake began in 2001, with an emphasis placed on tweaking and upgrading the visuals at the forefront. Utilizing the power of the GameCube, it was rebuilt from the ground up with Mikamki’s team utilizing new 3D models on top of high quality pre-rendered backgrounds. Live action cutscenes were replaced by animated full-motion videos, while character models received an upgrade through the use of motion-captured actors.

All of the original dialogue was rewritten and re-recorded with new voice actors. There are still homages to some of the more classic lines, but the overall quality of the dialogue is leaps and bounds better than the first time around. A new soundtrack was also composed by Shusaku Uchiyama (with Misao Senbongi and Makoto Tomozawa) to better accommodate the game’s horror aesthetics. The fixed camera angles and tank controls synonymous with the franchise were maintained, although a few new features were added, including the ability to quick turn and use defensive weapons when grabbed by enemies.

It is important to note, however, that the remake of Resident Evil was much more than just a graphical and audio upgrade. Concepts that had to be cut from the original release were reintroduced, with new areas such as the graveyard at the back of the mansion, which was not included in the 1996 release. Mikami also readded a subplot involving Lisa Trevor, the daughter of the Spencer Mansion’s architect, who had been kidnapped and experimented on by Umbrella for decades.

Lisa stalks around certain locations of the game, cannot be killed, and is extremely deadly, able to kill players in only a few hits. Another new enemy addition came via the Crimson Heads. Upon killing a zombie via any method but a headshot, the body remains dormant for a time. If not burned, it will eventually reanimate as a new, fast-moving zombie. This forced players to think twice before killing every zombie in the game, encouraging more strategic planning and outright avoiding some of the game’s enemies.

Following a final two-month crunch in which the developers worked endlessly without any days off, the Resident Evil remake met its deadline and was released in 2002. It received near-universal acclaim, selling over 400,000 units by 2004, an impressive number considering it was exclusive to the GameCube. By 2008, over 1.35 million copies had been sold.

The Resident Evil remake has gone down in the history books as the example of a near-perfect remake, something that only enhanced and accentuated the best parts of the original game while staying true to its vision and survival horror roots. The game was later ported to the Wii in 2008 and was itself remastered again in 2015 in high-definition for modern consoles and PC, with Capcom adding a new control scheme option allowing players to bypass the tank controls. This new remaster has sold an additional 2.4 million copies as of September 2019, cementing the franchise as one of Capcom’s most lucrative properties.

With seven games in the mainline series, including two remakes with a third on the way, numerous spin-off titles, and a live-action movie franchise, not even Capcom could have predicted just how popular the game would become. 2002’s Resident Evil will always stand as a testament to Shinji Mikami’s vision and exactly what Capcom is capable of, providing fans both old and new with a rewarding experience.

Following the success of the remake, many fans assumed that Resident Evil 2, released for the PlayStation in 1998, would be the next game in the franchise to receive the same treatment. It seemed like a logical step, as many considered the first remake to be a masterpiece in its own right. If the sequel was to receive the same attention, surely it would be too.

With the release of Resident Evil Zero later in 2002 (along with its eventual port) and the massive success of the more action-oriented Resident Evil 4 in 2005, Capcom decided to take the series in a different direction. It wouldn’t be until 2015, thirteen years after the first remake, that the publisher would announce to fans “we do it” in regards to a Resident Evil 2 remake. That release finally came in January of 2019 and impressed many fans of the franchise, including our very own Chris Morse, who wrote a review of the title last year.

Join us in the next segment as we explore Resident Evil 2 from its inception, to the cancellation of its original concept, its many unique ports, and finally the then-long-sought-after remake.

More Reading

Resident Evil 3 Remake Review: A High-Octane Last Escape

Capcom's latest survival horror remake dials up the action, but not at the expense of gruesome imagery and terror.

Weekly Horror News Round-Up March 28: Resident Evil 3, The Last Drive-In, Into the Dark

Plus, the coronavirus continues to create delays, Castlevania gets renewed for a fourth season, go behind the scenes of Penny Dreadful, and more.

Weekly Horror News Round-Up March 21: Resident Evil 3, What We Do in the Shadows, More Coronavirus Cancellations

Plus, Simon Pegg and Nick Frost reunite for a PSA, Universal offers up some early home video releases, a few new trailers arrive, and more.

Weekly Horror News Round-Up March 7: Resident Evil 3, Lucifer, Stranger Things

Plus, the first teaser for What We Do in the Shadows Season 2 is here, the Antebellum trailer debuts, a classic Castlevania heads to mobile, and more.